Most animals in nature all look alike within a species: budgies are green, relatively the same size and conform to a standard "normal budgie" look. Animals are very similar within a species because evolution has carved them into a pattern that works. Giraffes have long necks to reach tall branches and their color matches the surrounding environment. You don't see many purple giraffes out there. A mutation is a naturally occuring difference from the norm. Every so often an animal will be born that is slightly different from the rest. Most of the time this mutation works against the animal. If a giraffe was born with a short neck it would quickly starve to death. But occationally a new mutation can be beneficial. In this case the animal would survive to breed and pass its genes containing the mutation on to its offspring. A typical mutation you'll see pop up in wild bird populations is lutino. Mutations provide genetic diversity.

How do we get so many darned mutations in captivity? Contrary to what some people think, mutations are NOT man-made, even those we see in captivity. Most mutations are recessive or sex-linked, which keeps them from showing up that often. Normal traits are usually controlled by dominant genes. We get our captive mutations through the patient work of breeders. When a new color pops up in someone's collection the breeder will usually encourage the parents to lay more in hopes of getting more babies of the color. These babies are then line bred, a controlled form of inbreeding. Line breeding helps isolate the gene and can also help the breeder figure out how the gene is transferred (recessive, sex-linked, etc.). All the colors in captivity are natural. Once a significant number of the mutation has been bred a good breeder will then mate the birds back to normal stock to increase genetic diversity and lower the chances of disease.

If mutations are so natural, why is it that lutino tiels have bald spots, albino tiels are small in size and different colored budgies seem more prone to tumors? These affects are the result of the line breeding done to establish a mutation. Unfortunately, other less desirable traits are easily passed on with so much inbreeding. A good breeder will try to eliminate these problems by breeding mutations back to normal colored birds without bald spots or of a large size.

Feather colors are controlled by pigments. Birds carry two types of pigments: a dark one and a yellow-orange one. These two pigments combine to give us all bird colors. I'll use two example species in this article: budgies and cockatiels. In budgies the normal combination is yellow and green with black trim. In cockatiels it is grey with orange cheek patches and (in males) a yellow head.

Mutations can cause a bird to be born without the ability to make certain pigments or only to make them in certain patterns or places.

Lutino

This is a sex-linked mutation that inhibits a bird from producing any dark pigment. Only the

yellow/orange colorations will show, the eyes will be red and the feet and beak will be pink.

Budgies and most other species will appear solid, vibrant yellow. Tiels will vary with their

amount of white. Some will have pure white bodies while others will show tinges of yellow.

Blue/Whiteface

Blue is a recessive mutation in which the bird produces no yellow/orange pigment. The areas that

would normally appear green are now blue and black all remains as normal. Cockatiels are unique

because they do not normally appear green so their version of the blue mutation shows no blue at all.

Instead they appear only grey and white. The cockatiel version of "blue" is the whiteface mutation.

In both species the eyes and feet remain dark.

Albino

The albino mutation is a combination of the the lutino and the blue/whiteface. Albino birds

produce no pigments at all. They appear solid white with red eyes and pink feet.

Pied

Pied is a recessive mutation in which the birds lack pigment only in certain patches. A green

pied bird will have blotches of yellow on its body. A blue or whiteface pied will have blotches

of white. These areas do not produce dark pigments. Pied birds can look very attractive or very

"dirty" or "messy" depending on how these areas are arranged. Birds that are carrying the gene

for pied but not displaying it usually still have some identifying marks. Split for pieds may

have one or two light colored toe nails, a spot on the back of the head or one miscolored tail

feather. However, keep in mind while looking for splits in rosellas and kakarikis that these birds

normally have a lighter patch of feathers on their nape, though not always visible.

Cinnamon

Cinnamon is a sex-linked mutation that mutes the colors on the bird. It varies in its affects

per species. Cinnamon budgies look attractive. Cockatiels in particular look nice because the

grey areas actually take on a cinnamon brown color. Cinnamon turns the vibrant green of kakarikis

into a sickly pea soup color. Some breeders avoid the mutation completely in their collections

specifically because of its dulling abilities with color.

Pearl

Pearl is another mutation that is unique to cockatiels. It is sex-linked and has very interesting

affects. Pearl gives cockatiels a stripped or spotted appearance on their feathers. Hens

keep the coloration all their lives while males lose the pattern with their first molt giving

them a normal appearance. This makes adult male pearls difficult to locate. Pearl is

particularly attractive when combined with other mutations like cinnamon, whiteface and pied.

Spangle

Spangle is a very attractive pattern mutation in budgies. It replaces the typical black barring

with thin grey outlines. Spangles are usually very pastel as babies but the color darkens as they

get older.

Yellowface (budgies)

Yellowface is a mutation in budgies that allows yellow pigment in some locations but not others.

A yellowface may have a blue body (lacking yellow pigment) and a yellow back and head.

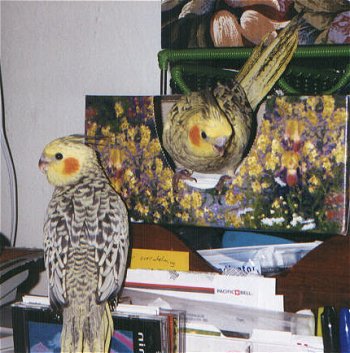

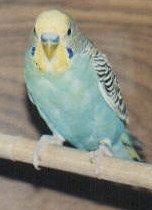

Of course there are tons of other mutations and combinations of them but they can't possibly all be covered here. Now let's test your knowledge of color mutations. Look at the following images and write down what mutation you think they are. Scroll down to the bottom of the page to find out the answers. Some are very hard! A few contain mutations we haven't covered here and others have far off views. Try your best.

Time to break out the punnet squares again! So now that you know the mutations, how do you predict what you'll get from certain pairings? How do you make predictions for more than one mutation?

Predicting more than one mutation involves a more advanced version of the Punnett Square which unfortunately I forgot how to do. Until I can dig up the method again use the following site to determine your probability of chicks. It allows you to enter the mutations of the parents and will tell you the possible outcome of chicks. Though designed for cockatiels, you can use the site for other species as well. Just pick a mutation that is carried in the same way as the one you want to predict (like whiteface for blue). Sorry for the inconvenience.

Keep in mind through all of this that punnet squares can only tell you the probable outcome of a clutch. This may not be what you get! Take the clutch below, which had a probable 2 normal birds (both sexes), one split male and one pearl hen. All four eggs hatched pearl females.

A. Lutino

B. Pied

C. Blue pied

D. (Back to front) Yellowface albino, yellowface blue spangle, yellowface blue split to

pied, and yellowface blue. Yellowface albino is similar to cream albino in Indian ringnecks. It

is an "albino" bird that has a yellow wash over it's body. The split to pied bird has a yellow

spot on the back of his head (barely noticeable). In real life he also has one white tail

feather (not visible here).

E. 1 & 2 are green pied; 3, 4 and 8 are yellowface blue; 5 is that split to pied male

again (head spot clearer here); 6 is a cinnamon green and 7 is again the yellowface albino.

All articles and images contained on this site are © 1998, 1999, 2000 by Feisty Feathers unless otherwise noted and may not be reprinted or used in any way without the author's permission.